Paraquat

Overview

Paraquat is an extremely toxic herbicide which may produce multisystem organ failure and pulmonary toxicity from as little as one mouthful of 20% concentrate.

There is no specific treatment and any hope of survival rests on preventing absorption. There is a suggestion that early haemodialysis may improve survival. Immunosuppression with dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide and methylprednisolone is widely practised, but evidence for efficacy is very weak.

Antioxidants such as acetylcysteine and salicylate might be beneficial through free radical scavenging, anti-inflammatory and NF-κB inhibitory actions. However, there are no good quality published human trials.

Mechanism of Toxic Effects

Ingestion of paraquat leads to the generation of highly reactive oxygen and nitrite species resulting in toxicity in most organs but the toxicity is particularly severe in the lungs and kidneys where paraquat is taken up against a concentration gradient.

Paraquat can induce apoptosis by production of ROS and activation of NF-κB. This leads to nuclear condensation and DNA fragmentation. These free oxygen radicals cause lipid peroxidation, damaging cell membranes and leading to cell death. Lipid peroxidation is considered by some to be a key initial pathophysiological process in the cascade of events following paraquat poisoning, although the primary importance of this mechanism is not universally accepted, with others postulating these effects follow other pathological processes. Free radical scavengers such as glutathione are rapidly overwhelmed due to the efficiency of paraquat in generating free radicals.

Paraquat is actively taken up into type II pneumocytes and renal tubular cells. Thus, in less severe poisonings, renal and pulmonary toxicity as well as direct gastrointestinal effects are the major clinical manifestations. In poisonings that are not fatal within days, the pulmonary fibrosis that develops is due to an acute pneumonitis that leads inevitably to generalised alveolar fibrosis. Increasing concentrations of inhaled oxygen increase pulmonary toxicity presumably by enhancing oxygen radical generation. About half of those patients who survive long enough (6–9 days) will develop a mild hepatitis.

Risk Assessment

Any ingestion of paraquat is potentially fatal with deaths reported following ingestion of less than 1 mouthful. Ingestion of >50-100ml of 20% concentrate can cause rapid multisystem organ failure and death.

Kinetics in Overdose

Absorption:

Paraquat is rapidly but incompletely absorbed. It is primarily absorbed in the small intestine (poorly from the stomach) and its absorption rate is estimated to be 1–5% in humans over 1–6 hours, and the rest is eliminated through defecation. Absorption is decreased in the presence of food. Plasma peak concentrations in humans are attained within 30 minutes to 4 hours; concentrations decline rapidly over the first 15 hours as it is redistributed to tissues. There is little absorption through intact skin or via inhalation.

Distribution:

Paraquat is rapidly distributed to lungs, liver, kidneys and muscle. It has a volume of distribution of 1.2–1.6 L/kg. The volume of distribution is large as it is concentrated inside cells, particularly type II pneumocytes. Distribution occurs rapidly with substantial distribution within the first few hours. During this period, concentrations of paraquat in lung tissue rise progressively to several times that of the plasma concentration.

Metabolism:

Paraquat is not significantly metabolised into less toxic metabolites, instead undergoes reduction to a paraquat mono-cation radical (PQ.+) by enzymes NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, xanthine oxidase, NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase and nitric oxide synthase. PQ.+ is reoxidised to PQ2+ generating superoxide anions (O2.-) hydroxyl free radicals (HO.). These combine to generate peroxinitrite (ONOO-) a very strong oxidant and nitrating intermediate. This process regenerates the paraquat molecule allowing continuous redox cycling.

Elimination:

Paraquat is primarily excreted unchanged in the kidneys through renal tubular excretion. 90% of absorbed paraquat is excreted within 12-24 hours of ingestion, the remainder over days to weeks as it redistributes out of tissues. The initial elimination half-life is around 6 hours, but after 24 hours this drops to 4 days.

Clinical Effects

The initial presentation is with gastrointestinal toxicity. In severe poisoning this is followed by multiorgan failure and, if patients survive this phase, by the slow development of pulmonary fibrosis leading to hypoxia and death.

- Gastrointestinal effects: Concentrated paraquat (20%) is corrosive and has direct gastrointestinal toxicity leading to oesophageal and gastric erosion as well as burns in the mouth and throat (‘paraquat tongue’). These corrosive effects are similar to that observed with alkali ingestion. Mucosal lesions in the oesophagus and stomach may result in perforation and mediastinitis.

- Pulmonary Efects: Ingestions of small quantities will lead to progressive development of respiratory failure. The onset of pulmonary fibrosis may be delayed for days to weeks and death may occur up to a month or more after ingestion

- Multiorgan failure: If more than 15-20ml of paraquat are ingested then multiorgan failure rapidly ensues. The major manifestations of this are:

- Acute renal failure

- Hepatic necrosis

- Myocardial necrosis

- Acute pneumonitis

- Internal haemorrhage

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Paraquat oral changes approx 3 days post ingestion

- Chest x-ray showing alveolitis approx 5 days post ingeston

- CT chest showing lung fibrosis approx 1 year post ingestion

-

Investigations

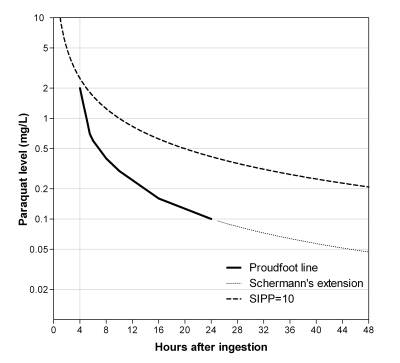

- Paraquat blood concentration: Plasma concentrations for paraquat are important indicators of prognosis with a plasma concentration >5mg/L at any time indicating an invariably fatal outcome. A paraquat nomogram has been developed indicating the chance of survival (See Below). Paraquat levels, are not available in many settings, and when they are they often are not available in a clinically useful time frame (several days) and treatment should not be delayed while awaiting a level.

- Qualitative dithionite urine test for paraquat: This simple test, if positive indicates exposure to paraquat. 1ml of 1% sodium dithionite solution is added to 10mL of urine. A blue colour change indicates paraquat ingestion. If this test is negative on urine passed 2-6 hours after ingestion it indicated that a significant exposure is unlikely. Information regarding the test can be found here.

- Other investigations:

- Full blood count

- Coagulation studies

- Serum electrolyte and creatinine concentrations

- Liver biochemistry

- Blood gas analysis and blood lactate concentrations

- Chest X-ray

- ECG

Paraquat seum level vs time since ingestion. Serum levels above either line predicts low probability of survival.

Treatment

Supportive:

Airway and breathing

Patients with moderate poisoning may benefit from good supportive care. Mild to moderate hypoxia should not be routinely treated with oxygen as this will worsen oxidative stress and greatly increased lethality in animal models. Oxygen should only be administered if arterial oxygen saturations fall below 90%.

Early intubation may be indicated due to the risk of upper airway swelling, respiratory depression and hypoxia.

Circulation

For hypotension, first line treatment is intravenous fluid resuscitation.

Decontamination:

Early decontamination is essential and should be given as soon as possible.

Give: 50g Activated Charcoal (Child: 1g/kg, max 50g) immediately to all suspected ingestions and repeated 4th hourly if tolerated. Fuller’s earth can be given if activated charcoal is not immediately available. If neither are available a slurry of 100g of soil with water can be used instead.

Enhanced Elimination:

Early haemodialysis may reduce toxicity, particularly if started within 2 tof ingestion, prior to redistribution into tissues. DIscuss with a toxicologist.

Antidote:

There is no antidote for paraquat poisoning.

Current treatment recommendations aim to reduce oxidative stress and the inflammatory response, and increase paraquat transport out of cells. There are no good quality randomised trials supporting these recommendations.

Acetylcysteine

Acetylcysteine (NAC) is used as antioxidant therapy. An extended regime for the duration of admission is recommended. A standard 2 bag regime is used, with bag 2 given back-to-back until fit for discharge from hospital.

Give:

Bag 1: 200mg/kg NAC (max 22g) in 500ml 5% dextrose over 4 hours

Bag 2: 100mg/kg NAC (max 11g) in 1000mL 5% dextrose over 16 hours

In children bag 1 should be given in 7ml/kg of fluid (max 500mL) and bag 2 in 14ml/kg (max 1000mL).

NAC can be given in 0.9% NaCl rather than dextrose if hyponatraemia is a concern.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are used for their anti-inflammatory effects.

Give: Methylprednisolone 1g (Child: 20mg/kg upto 1g) IV daily for 3 days, followed by dexamethasone 8mg (Child: 0.2mg/kg up to 8g) orally every 8 hours for 5 weeks.

Observation and Disposition:

Admit patients who have ingested any volume of paraquat for at least 24 hours, even if they are asymptomatic, with repeated key investigations prior to discharge.

Those who are symptomatic but survive the first week may still develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis up to six weeks later. They should have regular follow-up with chest X-rays.

Asymptomatic patients who have had skin or inhalational exposure to paraquat are unlikely to have significant poisoning and can be discharged after 6 hours of observation.

Educational Resources

Further Reading

- Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Duarte JA, Sánchez-Navarro A, Remião F, Bastos ML, Carvalho F. Paraquat Poisonings: Mechanisms of Lung Toxicity, Clinical Features, and Treatment. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2008;38(1):13-71. PDF

- Delirrad M, Majidi M, Boushehri B. Clinical features and prognosis of paraquat poisoning: a review of 41 cases. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(5):8122-8. PDF

- Gawarammana IB, Buckley NA. Medical management of paraquat ingestion. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2011;72(5):745-57. PDF

- Senarathna L, Eddleston M, Wilks MF, Woollen BH, Tomenson JA, Roberts DM, et al. Prediction of outcome after paraquat poisoning by measurement of the plasma paraquat concentration. Qjm. 2009;102(4):251-9. PDF

- Gawarammana I, Buckley NA, Mohamed F, Naser K, Jeganathan K, Ariyananada PL, et al. High-dose immunosuppression to prevent death after paraquat self-poisoning – a randomised controlled trial. Clinical Toxicology. 2018;56(7):633-9. PDF

- Pond SM, Rivory LP, Hampson EC, Roberts MS. Kinetics of toxic doses of paraquat and the effects of haemoperfusion in the dog. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1993;31(2):229-46. PDF

- Jones AL, Elton R, Flanagan R. Multiple logistic regression analysis of plasma paraquat concentrations as a predictor of outcome in 375 cases of paraquat poisoning. QJM 1999; 92: 573–578. PDF

- Gao Y, Zhang X, Yang Y, Li W. Early haemoperfusion with continuous venovenous haemofiltration improves survival of acute paraquat-poisoned patients. J Int Med Res 2015;43(1):26–32. PDF